A Short Story

THE FIRST REPORT

He came in from the cold.

She asked the usual questions when he came in to help her with her youngest daughter’s children: was it cold out there? Still minus-minus? Did we get some mail? He kissed her hello and said, Yes, it is cold. Yes it is still minus 12 Celsius. Yes, I got your mail – bills and statements from our banks. Junk mail. One for me, though. Reader’s Digest’s announcement that I am finally a contender for the million dollar jackpot, and another, I think, from Old Age Security, or pension, or something, he mumbled. He tried to be cheerful, but he mumbled.

His 30-minute walk through the chilling streets from their townhouse left him breathing hard. Like a wheezing old man. Like the wheezing old man he has become, really. He called it his “constitutional”, but everybody knew (his family in Canada) that he had to be there before lunch so could eat with her, and be off with her car to the other daughter’s house to sit for still another set of grade school girls. Saucy ones who were always fighting.

He did not have his own car, and he must depend on the functional Japanese car parked where she left it, coming in earlier to relieve her youngest-teacher-daughter who must run to her class. She’s late. The engineer-husband had to commute. Bad traffic. He’s late.

The walk did him good, though. He needed the long, daily walk, to cut through his enervating depression. Or to take his mind off his ageing ailments, his aches, his IBS, his occasional chest pains, tingling left arm, crinkly fingers, forgetfulness, and obsessive compulsive symptoms of Alzheimer’s, etcetera. He goes through this list with his bemused physician, the Chinese family doctor at the mall, every time he consulted him. It was often, of course, because it was free. Won’t get this in the old country, “un ventaje, hombre!”, his wife would drill this health-care advantage into his head – if she was lucky to say it to a good ear. He did not wish to immigrate to this cold country, in any case. Nor dreamt of it.

He said he also needed it to think. To keep his porcine heart valve working, he must do all that walking, his only son would tell his kibitzing sisters.

He coughed. He came in from the cold. He will be fine.

His “tesoro”, the one he calls Nicky 2, stopped her “Dora the Explorer” TV session, and ran into his arms” ‘Lolo! ‘Lolo! I’m watching “Dora”! She ran back as quickly as she appeared at the door. Where’s, the big, bad boy, he asked, pretending to look for the younger sibling, his “assignment” in this babysitting partnership.

The chubby boy remained motionless in front of the idiot box, ignored his inquiring abuelo (No ‘Lolo!-‘Lolo!- yelled-greeting this time. No hugs, no kisses. Just a mindless act of ignorance that felt like a freezing icicle between his testicles. Watching Dora, he protested when the old man made his mock-call: O, Louie, whey ah youoooo?

Have you had your merienda, he asked the reception line, now transformed into a puttering woman rushing through the preparation of a pot of chicken stew. Not yet, not yet, was the harried response. She called out to the boy: go kiss your abuelo or no cookies for you! No! was the prompt retort from the motionless boy in front of the idiot box.

He saw she saved some of the crispy fried chicken skin for a snack. She plunked the saucer of skin on the table, muttered for him to sit down for his snack, and, with an unctuous tone she said, after lunch, let’s talk. Let’s talk. That was like stalactites shoved up his frozen ass. It occurred to him that she was issuing another warning: Let’s talk, asshole!

He knew this was coming. One of those “fearsome” ones. She lay sleepless last night, fuming that he had this talent of taking the joy out of everything, even out of the late television show. I know it’s late! I know I’d be sleepless. But do you have to harass me? He promised that they would not go to sleep fighting. Well, she hated him, she said last night.

Let’s talk. He did come in from the cold.

After a perfunctory, ominously silent lunch, he quickly washed the pots and pans, dishes, utensils, the children’s’ bibs, and anything she thought should be in the sink. Gary’s job, he muttered. Huh? She challenged. He snickered, snorted really, and said, that’s the South Afrikaner’s name, remember? The Disney Cruise waiter, remember? He hastened to explain lest she fly the handle for his insolence. Huh! The guy who did not do a good job, she said. I’d get that label as his second fiddle, she said, she being the Mario, the main waiter on table 137 at the cruise. Some baby waiters, he said. Caregivers, hombre! She shot back. Besides, don’t you love your grandchildren?

Let’s talk. She said, we should get it over with before the children woke up from their mandatory naps. (A downtime for the sitters, uh, caregivers, all right?) It was going to be a long, painful one, he suspected. The last time she required this communication, she demanded that the almost 50-year marriage be done with, over – kaput. She said she could not take the moods anymore. Why are you so unhappy? Why have you become a hermit? You would not even want to socialize with your children. We have no friends in this country at all!

As soon as he slumped on the leather sofa which doubled as her napping bed, she asked the same questions again. This time, however, they were surprisingly doleful. What, no fury, he thought and got confused. The last time those questions were asked, he thought he lost his keys to the house. He was left twisting in the wind. She did not see the keys, she harrumphed. Was she getting ready to kick me out? If she changed her mind in his favour that time, she did not let on. A homeless husband is harder to explain to the children and grandchildren. Maybe.

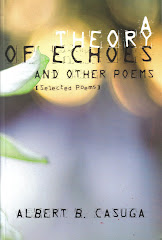

He felt so ineffectual. In the old country, he was a brilliant academic, a writer, a journalist, and author of books and scholarly papers. Now, I could not even write my epitaph! He sighed.

Even the children make fun of me. They speak to me like I was out-of-it, dumb. Or suspect that I only choose to listen to what or who I wanted to pay attention to.

And do we still touch each other?

He felt a tug at his sleeve. Are you sad, ‘lolo? Are you crying? I will protect you. The little girl’s voice was gentle and strangely solicitous. Those were words he whispered to her one summer when she wept over a dead bird in the now snow-bound yard. Then, she went back to her strewn toys, books, cups, saucers, plastic things. She was singing a French ditty. She was counting in Spanish. She was saying “mahal kita, mahal kita” to her rag doll. A quadrilingual delinquent one day? She must be listening. Little ears. But at three, she will remember. Why is she not napping yet, he asked the woman who had just wrapped an arm around him.

You have to move on, darling. Past is past. What you have achieved then is a large part of your life. But move on. There are more poems to write, more stories to tell. What about children’s books? She surprised herself with her mellow coaxing.

The tears were there. There were affairs. But they got back together. In this new country, she promised to build a new life for both of them. This was his covenant, he pledged likewise.

Why don’t we get you occupied with something you have always loved? Write me something everyday or every moment you get. It does not have to be a poem, a story, or play. Remember your notebooks? What about journals. Why don’t you start a memoir? Or just get into the business of writing once again. I’ll tell you what…Do your writing. Send me a copy of anything you have done. One click on the computer. Every day. You know, like writing a report. She stroked his wrinkled temple.

Because he could read the plea in her conches-like eyes, and the old ardent faith she would tell him about when his blocks would torture him no end, he asked: What could I give you in return for this kindness?

What about a 10-minute massage before we go to sleep? That should help me go to sleep. I do not sleep well, darling. I need to sleep.

The little girl kneeling by the fireplace let out a sudden shriek: I am not tired, ‘lola. I don’t want to sleep.

She took her little hands into hers and said: Go kiss your lolo, nighty-night. When you wake up after your nap, we will have hot chocolate. Deal?

Nicky 2 moved hesitantly to the wheezing old man and said: Beso beso, abuelo.

He came in from the cold again the next day.

From the curve, he could see her and the little bobbing heads. They were waving at him. Blowing him kisses.

When he got to the door, she did not ask for the mail. Nor the weather. She wanted to know if he had the “report.” See your email, he said.

When they sat down for a snack, precious minutes before the tandem feeding of the children, he asked: Do you know that the first time I saw your undies was when we were chatting in the living room of your old San Juan house ? You were wearing a striped pair of grandma panties. Your thighs were silken white, my mestiza!

She gasped. Aiee, loco de cabeza! The children will hear you. She snickered.

He knew she blushed, but he continued: And my most cherished moment was that time you asked me while we kissed saying our stolen, endless goodnights, before your father would come down those stairs to signal my leaving, it’s midnight-you-know…was when you asked me if what you felt down there was a hard-on, and I said: it was a tumescence. You asked to see it. But it was dark, and we heard your father’s footsteps.

But that’s for another “report.”

--- ALBERT B. CASUGA

March 4, 2009

Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Israel launches missile strikes into Iran in response to Tehran's attack

Sunday

-

There are also reports of explosions in Iraq and Syria. The extent of

Israel's strikes weren't yet clear.

1 hour ago

No comments:

Post a Comment